This blog has moved. I’ve got a real website. With, like, my own domain name and everything! So take note and update your brains: this blog is now officially (and only) at www.aliteralgirl.com. Thanks!

–Miranda

This blog has moved. I’ve got a real website. With, like, my own domain name and everything! So take note and update your brains: this blog is now officially (and only) at www.aliteralgirl.com. Thanks!

–Miranda

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

This is exactly how I feel right now. I don’t mean right now in this moment; I mean right now in general. I mean this sums up the sense that I have constantly. I’m both scuppered and free. At any instant I may hit a brick wall or discover opportunity. In a way this is how things always are. Impossible, amazing. How do you reconcile the fact that you always want what you don’t have with the fact that you have something special? You don’t, because this is how we have always been, this is how we always will be. You just sit there and thing, everything is impossible, anything is possible. You think that until you don’t know what anything means anymore.

Then, I suppose, you go from there, wherever there is. Is that right? I don’t know.

What I do know is this: a few weeks ago, the Man showed me this article about luck. I don’t often react well to things that he shows me. Perhaps I’d like to think that I don’t need guidance; that I could do better; that he’s not-so-subtly trying to tell me something. In any case I want to see flaws in the articles he shows me, and I saw a thousand flaws in this one. I saw this one as a personal attack. If you’re naturally negative or naturally anxious (and who can deny that I am both?), I pretended the article was saying, you’re fucked. He tried to tell me that wasn’t it at all, but I was in a foul mood, and I’d convinced myself, and that was that. (That’s always that).

But then last night he said to me, you’re more positive lately than you have been. You’re happier. It’s nice.

Yes, it is nice, and yes, I am, and no, I don’t know what it’s related to, exactly, but I do know that on the “everything is impossible/anything is possible” scale, I’m leaning towards the anything is possible side. What this means, specifically, is vague, and hardly matters. What it means generally is what he said. More positive. Happier. Nice. Everything is so bloody hard. And at every moment there’s the possibility of something. I can just about deal with that. I can just about feel the tremble of possibility. Who can say what luck’s got to do with it?

*Thanks to a good friend for helping me work this one out tonight…

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

I’m a fan of the to-do list. A big fan. Partly I like making lists because they give me something to do during the day that is about work but not actually work, if you see what I mean. I can just about get away with making endless lists of shit-to-get-done in the office because, in theory, once I’ve made my lists, I’ll start actually doing the shit. (In. Theory.)

But also I like the poetry of a to-do list. Funny titles, clever bullet points, drawings, plans, a record of a day (a week, a month). The simple (buy new toothbrush) to the huge (finish manuscript). I don’t make distinctions between the importance of different tasks; I might well buy a new toothbrush this evening, but equally I might well decide that my teeth can stay covered in plaque for the sake of writing another chapter.

My lists are not organized; no, this would be missing the point. The point of a good to-do list is not really to create order. The point of a good to-do list is to give thoughts some space. A good to-do list is like the Pensieve in Harry Potter (yes, really)–it’s like pulling thoughts out of your head, putting them somewhere safe, where they won’t bother you and you won’t bother them, and then being able to revisit them whenever you want.

A good to-do list cannot be made to look neat or tidy. At any moment you might need to add to it or subtract from it. You might need to write, “make new to-do list” on it because it’s so crowded; but you won’t make that new to-do list, not immediately. You’ll know when it’s time, when your priorities have shifted, when the clutter outweighs the usefulness of the list. Then you’ll start again.

Posted in Anxiety, Lists | 1 Comment »

Not often, but sometimes, it occurs to me that I am very, incredibly, out of touch with the rest of the world. It has always been thus, but living in Oxford makes it easy to forget that once I was a geeky Converse-clad girl with a bad hairdo. (I am now a geeky Converse-clad girl with a better hairdo. And sometimes I wear boots.) My life has become something completely ridiculous, in a rather wonderful way. Take this, for instance: one of the highlights of my existence is the rush I get when I swipe my card at the Bodleian and open my bag so that they can check to make sure that I’m not trying to smuggle a bottle of water in and walk up the stairs and smell the books. And there are all these other people there! Doing the same thing! Loving the books! And outside (this is the best bit) there are a bunch of tourists who can’t come inside. It’s a perverse (and very British) revenge of the nerds; and I’M PART OF THE CLUB! I actually have a special walking to-and-from the library swagger. Just so that everyone will know that I belong. (Sometimes, but not often, I even manage to swagger without tripping over my own feet.)

Posted in Books, City, Oxford | Leave a Comment »

And then there was the time we hid under my parent’s bed so that she wouldn’t have to go home. I don’t know why I remember this now, particularly. There are children playing hide-and-seek in the house (not our children, not our house). I guess somehow that makes me think of this one afternoon, a long time ago. A friend of mine had been over for the day, and now her mother was coming to pick her up and we did not want this to happen. Somehow every time a friend was picked up by a parent, it seemed like it would be the last time we would ever have such a chance to play and be carefree. I remember tears and tantrums; perhaps it was a manifestation of only-child loneliness, perhaps simply a particular quirk of character, a shimmer of the anxiety and self-doubt that was to come.

But this friend (another only child) seemed to understand; and then her mother arrived, and it all seemed too awful. I can’t remember who suggested it first but suddenly we were under the bed in my parent’s room. I don’t know where our mothers were; perhaps they were in the living room, having a coffee and a chat, oblivious to our plan, thinking we were playing quietly in my room until the very last moment when we would have to be parted. But I know that after a time they called for us, and we didn’t come, and that was okay; most of the time, children don’t come the first time you call. But then they called again. And then, eventually, they scoured the house for us, and then in panic they ran out into the street and began to ask the neighbours, have you seen our daughters?

And the more we could hear their panic the more frightened we became of revealing ourselves. We wanted to crawl out from under the bed, but we couldn’t. We couldn’t face the shame. We would be in so much trouble. We had done something so very wrong, and out of such an innocent motivation. We scarcely knew how it could all have become so complicated so quickly.

We were in trouble, of course. We suffered both the wrath and the relief of our parents. Then, after awhile, we weren’t in trouble any more. After awhile we were older and after awhile longer we were living in different cities and hardly even knew each other any more. But still, we’d done something very foolish together once.

And now here I am in a thatched English cottage, thinking of that day. Things are funny.

Posted in Writing | 1 Comment »

I’m no longer just your average blogger/wannabe writer. I am now the official runner-up of Oxford’s very first Literary Death Match.

Oxford’s very first what now? Literary Death Match. Half crazy, half brilliant (isn’t anything worth doing a little bit of both?), cooked up by Opium Magazine‘s Todd Zuniga, the ultimate goal of the Literary Death Match is “to showcase literature as a brilliant, unstoppable medium”. I’m willing to get behind that.

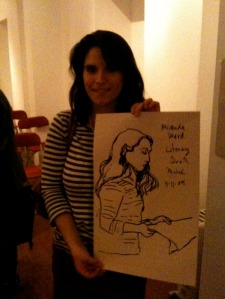

And get behind it I did. Along with fellow competitors Megan Kerr, George Chopping, and Jake Wallis Simons, I read an 8-minute long piece of writing to a friendly audience and a panel of judges, including award-winning poet Kate Clanchy, author and Idler editor Dan Kieran, and songwriter extraordinaire Ben Walker, at Oxford’s Corner Club. The lovely and talented Badaude, meanwhile, did a series of live sketches (including the one I’m holding at the top of this post!), and Xander did his producing thing.

After our readings, the wonderful Mr. Chopping and I were selected to go head-to-head in the final competition: a grueling game of musical chairs. Yes, musical chairs. With teams pulled from the audience, we danced round and round a series of chairs to the sound of Ben’s guitar. My team put up a good fight, but ultimately the hard-earned medal (and yes, there really is a medal) went to George (whose reading was, as always, superb).

It felt nice to be surrounded by so many talented, supportive friends and strangers. In particular, all the contestants deserve appreciation. It’s a nerve-wracking experience, reading aloud–even more so when the setting is competitive. But the mood was relaxed and gentle and the room was full of talent. Hopefully this was only the first of many Literary Death Matches in Oxford. In the meantime, I’m clinging to my title with pride and brushing up on my musical chairs tactics.

And, for the official LDM Oxford write up, visit this page…

For a few nice images of the evening, check out Garrett’s photos…

Finally, here’s what I read. Some of you may recognize it as being related to my posts on Devon and Dorset from September…

Fish, Chips, and Fossils

We head south, past Stonehenge, into Wiltshire, then Devon. Like Withnail and I, I think, only with slightly less booze, and a girl in the back seat, and two guitars, and several laptops, and lots of sunshine.

It’s slow going near the standing stones but otherwise we make good time, and by late afternoon we’ve started to move through villages with funny names—this is how you know you’ve reached somewhere rural, when every place becomes a pun.

We decide we’re lucky not to live in Chard, which is as bland as its vegetable equivalent, though the sunlight renders it almost poignant. We drive through Lower Sea Fields, pass car dealerships and pubs, a petrol station simply called “POWER”, a street called “The Street.” We say how glad we are to live in Oxford, with its literary ghosts, its haunting spires; but then, we’re trying to escape, aren’t we? We’re young and running away from jobs we hate. We think a few days near the coast, away from the ghosts and the spires, will fix us. The Musician, the Man, and me. We’ve found a couple in an East Devon village with a cabin for rent. We think a cabin sounds quaint.

In Musbury, we turn up into the hills, onto a single-track road lined with hedges and gates. We’re met by our hostess, who wears fishnets under her shorts, tells us she’s celebrating 35 years of marriage tonight, and shows us how to turn the hot water on. On the bookshelves are various slim, brightly-coloured volumes with titles like, It Shouldn’t Happen to a Missionary and How I Fell In Love With The Church and Out Of Love With Communism. A sign near the toilet forbids us to do various things. Do not dye your hair. Do not bleach your hair. Do not smoke. Do not flush tampons down the toilet. Do not deep-fat fry anything.

We buy pasta and red wine for dinner at the village shop, and then that honing device buried within the heart of every British male switches on and we’re heading towards the pub.

“How do you know the pub is that way?” I say.

“It just is,” my companions tell me.

They’re right, of course. And inside it is a miracle; it is 1956, minus the fog of cigarette smoke. We sit outside in the sun watching the pub sign swing on an evening wind.

We linger until the light wanes. Heading back up the hill to the cabin, we pass a cat lying in a lane, watching with intense concentration what appears to be an enormous pile of horseshit. We take a photo of the cat watching the horseshit.

In the morning I wake and sit on the swing in the garden. A few apples drop down behind me. There is a curious braying in the distance, like children or cows. Then, gradually, the sound of hooves, and a bugle. The hunt glides past. Over the hedge we see bowler hats. We hear a man shouting “Wendy! Wendy! Come HERE, Wendy!”

Is Wendy his wife or his hound, we wonder? We ponder this for some time, over coffee and bacon. Wendy is probably the name of both his wife and his hound, we decide.

We set off for a local festival. We’re greeted by a cider tent and a queue six miles long. We join the queue, which isn’t moving, and has, as far as we can tell, no actual purpose. From our vantage point halfway up a hill, we can see that the line of humans simply peters out.

“What are we queuing for?” someone—a novice—asks.

“I don’t know,” someone else says cheerily. Nobody moves.

Presently we decide we’ve queued pointlessly for long enough, so we stroll through the gates. At the centre of everything is a red-and-white striped tea tent, serving cream teas, home-made jams, and complimentary cordial. A few suicidal bees dive into the jam; isn’t it a bit early for that? I ask them. But parents are already sucking on their cups of cider, and infants are writhing and laughing, and one particularly excited little girl is simply running around in circles like a puppy chasing her own tail, so why not, I think.

My attention is arrested by the “Border Collie and Duck Display” near the tea tent; we watch for awhile as a lithe young border collie attempts to guide a gaggle of very upright black ducks into a wooden cage and fails. We watch the ferret races. Or at least, we watch one ferret make its lazy way to the end of a very short course while the other two sniff around at the starting gate and refuse to move. We join another queue for lunch (this is the great English pastime!). “No, you can’t just push to the front darling…” one mother tells her hungry toddler. “…we’re British.”

The next day we go hunting for fossils. Past the endless stream of caravan parks in Charmouth, we reach a rocky section of the Jurassic Coast renowned for its ammonites. They’re common as pebbles, all the signs and brochures promise. You’ll be stumbling over them.

But we don’t stumble over anything. We sift through the rocks; we scrape them with our feet and sometimes, to make ourselves feel as if we’re doing something, we actually pick up a rock and split it open against another rock, then sadly discard both halves. I find what might be Fool’s Gold, what might be a tiny ammonite, and a smooth amber-coloured rock that feels good in the palm of my hand.

On our last full day, we drive again to the coast. We start with Seaton. Sleepy doesn’t even begin to describe Seaton. It’s comatose. And, like Alex Drake in Ashes to Ashes, it’s woken up in an alternate-reality version of 1981. Handwritten signs saying “RIP Seaton” are plastered on windows all around town. There are shops selling antique tat, shops selling general tat, shops selling general tat and also some old records, a grocery store and a chemist. There are two pubs, both on the verge of falling over. And there are 495 fish and chip restaurants.

So we decide we’ll have fish and chips in the wind on the beach. At “Fry-days”, we order and then watch the diners slowly finishing lunch. We are the youngest people in the room by at least 50 years, and everyone appears to have ordered the exact same thing: cod and chips, followed by weak, sugary tea. They all chew at a glacial pace; one woman nods off midway through a bite of peas, is startled back to sentience by her husband’s warbled plea for the vinegar.

We take our boxes down to the edge of the water, nesting amongst the rocks with our backs against a concrete wall so that we don’t have to look at the town itself. From here it’s almost beautiful: the beach is open and bland; the sea pale and windswept. My fish drips with oil and the mushy peas are especially mushy (pre-masticated, perhaps, for the benefit of the toothless).

After, we lie back exhausted on the stony beach, as if it’s been a great effort just to consume so much fat. I wash my hands in the sea. Our minds are heavy with sleep and our hearts drooping with a strange kind of sorrow for this dying town, and its dying population.

We make our way back to the car via a few shops. One sells jewelry, old tables and chairs, fossils, used postcards, model cars, glass bottles, old beer mats. I buy an edition of Browning’s poetry, a collection of essays, a volume of Modern English Usage from 1926. We find a book entirely devoted to the Dewey Decimal System, which once, a stamp inside informs us, belonged to the Sexey Boys’ School.

We don’t hold out much hope for neighboring Beer. Surely the novelty of the town will merely be in the name–but we feel we must go, anyhow, so that we can make all the requisite puns, so that we can say to our friends when we return that we had a beer in Beer, ha ha ha.

Beer turns out to be a handsome village tucked into a hillside, with a steep ramp leading down to a beach teeming with fishermen and boats. We buy two fresh plaice and spend a few minutes making plaice jokes (”looks like we’ll need plaice mats tonight,” I say).

We have a cup of tea in a garden overlooking the sea, and remember our awkward youths. We were uncomfortable, geeky kids: black painted nails, Doc Martens, computer games. I recall with some chagrin a photograph of my 14-year-old self, in fishnet tights and dyed-maroon hair, staring seriously into the camera on the Fourth of July.

We drive back through Axminster. The sky is ripe for stars. The Chinese restaurant gives off a sickly glow and the pubs with their heavy lidded eyes yawn, dispel a lonely customer, take an even lonelier one in. Ah, these half-dead English towns, I think. These beautiful, tender, half-dead English towns.

Posted in Oxford, Writing | 1 Comment »

Last week, the lovely Academic, Hopeful tagged me in a meme-type post about folders and photos. An easy diversion, a good way to kick-start the blog again. Pick the 10th photo of your first folder of photos and post it. So here’s Greece, the summer I graduated from high school. My toes in the lower right-hand corner; a Vodaphone ferry taking off from the port at Parikia on Paros. I was sunbathing after a breakfast of yogurt, honey, and fresh fruit. I was reading either The Green Hills of Africa or Lady Chatterly’s Lover. I was recovering from a nasty cold, wearing a new candy-striped bikini I’d bought in town the day before. Look at that sky. That sea. It was the mildest water I’ve ever felt. It’s easy to fall into this photograph now, in the grey and gloom of an Oxford November. I wouldn’t want to be seventeen again, abroad on my own for the first time. Everything felt so intense–the colours, the tastes, everything I did, smelled, felt. The sunburn and the cool relief of an evening wind. I was over-saturated in experience. Still, it was beautiful, and still, on a night like this, only half-past-four and the darkness settling in, I think I could use a little nap in the sunshine.

Since we’re talking of sunshine, I’m tagging my mom, who writes this beautiful blog from her warm home in California…

Posted in Memes, Travel | Leave a Comment »

We tell ghost stories on the way home. It’s dark; Port Meadow is black, the river is silver and still. We have bike lights and a parafin lantern. A mist covers the ground, as if we’re wading through it. I can see my breath, feel the tingle of my fingers.

Earlier we walked the other direction. It was early afternoon, light, grey, the trees bent over the water. The dog picked up impractical sticks and we sipped from a small bottle of whiskey. Amazing how quickly we could be palpably outside the city. Smelling woodsmoke from narrowboats and surrounded by green and brown; the golden stones of Oxford had dissolved, the spires dissapeared behind a puffy cloud. My wellies rubbed raw a spot on my foot, the same spot on the same foot that had been rubbed raw so many times before. We came to a crumbling nunnery; now just a field walled in, the outline of a church. We ate apples at the pub and drank wine waiting for our lunch.

Now we tell ghost stories but there’s nothing eerie about this stillness. The eerie part is re-entering the city, coming suddenly to a well-lit bridge, passing parked cars, pubs, restaurants, cashpoints, closed shops, kebab vans. It’s crowded, though there aren’t many people out tonight.

Meanwhile, I’ll get back into blogging, but my time seems to be consumed at the moment by a thousand little things–working, writing, eating, sleeping, cleaning, running, planning. Strolling along the river. Stay tuned.

Posted in City, Country, Living Abroad, Oxford, Places, Seasonal, Travel | Leave a Comment »

I’m about to be a part of something really cool. Next month, I’m going to New York with Xander and Ben for a sort of tour 2.0-type thing. We’re calling it Man (hat on). There’s even a logo (and the likelihood of t-shirts). No, I’m not a musician. My misguided adolescent foray into the world of string instruments is likely as far as I’ll ever go, musically. But it doesn’t matter. Because–although there will be music involved (provided mainly by Ben, obviously), this is really a tour about freedom, and doing what you like, and creating things.

We’re playing with this idea of “sustainable creativity”, you see. It’s about using communities and ideas to sustain yourself, so that you’re able to do what you love doing. It’s simple, on paper: if you’re a writer, you find a way to write. If you’re a musician, you find the support you need to play gigs and write songs. If you’re someone without a clearly defined path, someone who just likes to play with ideas—it means finding a way to do that.

It sounds easy, but it isn’t. Creative output takes a lot of time, energy, love, and support, not only from the creator, but also from his or her community. The problem is that many of us are saddled with a lot of extra baggage. We have bills to pay and debts to pay off. We have social and professional obligations that rigidly divide our days. Very likely we’re burdened with a “real job”—which we may find intellectually dull and emotionally empty, but necessary nonetheless (I mostly babysit photocopiers and answer telephones grumpily, for instance).

And in an era where time is money, how do you justify spending a few hours every day on your craft? How do you find a few hours every day? It’s impossible to underestimate the negative power of financial constraints. If you constantly spend your time thinking, I should be making money, not fucking around, you quickly become creatively impotent.

So suppose we make things easier for ourselves. Suppose, to start, we surround ourselves with other, similarly minded, creatively charged people, and become a kind of micro-community based on the idea of mutual inspiration. This removes a number of barriers, and in their places, provides us with a number of opportunities. It gives us an automatic audience, a built-in sounding-board, a kind of creativity support group. It allows for collaborative effort and means that even an ordinary trip to the pub can result in a great idea. In a way, it combines the social aspect of our lives with the creative aspect, thus gaining us time as well as emotional backing.

Well, that’s good. That’s a source of motivation and stimulation. But we’re still stuck with that bland job, those pesky bills, all the worries that get us down. Even if we have a micro-community of like-minded creatives, we’re still not going anywhere. Not yet.

The next thing to do, then, is to give up the rock star dream. Forget, for a moment, that you want to be the next superstar of the rock n’ roll, or literary, or art, or whatever world. And remember why you started singing, or writing, or drawing, or playing with ideas, in the first place. Innovative solo bass player Steve Lawson writes prolifically, and very well, about this: “I no longer need to pretend to be a rock-star. The mythology of rock ‘n’ roll is nowhere near as interesting as the reality of creativity.” And, Steve adds, “The 80s dream of everyone becoming Stadium rock stars has faded, and more and more musicians are looking at fun ways to get to play music in a financially sustainable way.” And what we’re trying to say is: not just musicians. Anyone who wants to make anything should be listening to Steve on this point.

It sounds cheesy, but this is an idea about survival and satisfaction, not about making a profit, not about constantly striving, clawing your way up the celebrity hierarchy. This is an idea about how you can do what you love doing—what you would be doing anyway–and earn enough from it to justify doing it as something more than a hobby. To earn enough from it to recoup your costs, eat a meal or two. Eventually, to earn enough from it to pay all those bills, to live comfortably, to buy a new pair of boots (or the male equivalent) when you need to. But to start, it’s only about getting by.

Luckily, that built-in creative community—even if it’s just a group of two or three people—is the key. Gone are the days when any artist can continue to cling to the alcoholic outcast myth and hope that her lonely genius will be discovered. There’s just too much stuff out there for that to be a viable tactic. There are literally thousands of other musicians writing songs and putting them up on the Internet. Thousands of other filmmakers uploading clips to YouTube. Thousands of other writers with blogs. Thousands of other painters with thousands of canvases stacked up in their basement. And every single one of them can publicize themselves, advertise themselves, with the click of a button. Passivity and sheer luck may work for some; but the only way to guarantee a sustainable, creative life is to actively seek one out.

So you start with a tiny community. A few friends. Maybe you start at the pub, where ideas can flow unchecked by the ordinariness of daily life. And you realize that actually, there’s a lot of overlooked potential in the world. You buy some tickets to New York. You decide that you’re going to prove this theory by living it.

So we are three people, with different skills and ambitions but a common goal of creating things and doing cool stuff, taking a week off work. We’re going to pack up our guitars, our laptops, our brains, and head across the Atlantic, where we’re going to do what what love, and what we’re good at, and find a way to survive. We’re going to stay cheaply (with friends, on couches). We’re going to earn just enough to recoup our travel expenses, and hopefully have enough left over for a few beers at the end of the day.

There are, of course, one or two things that anybody sensible might want to ask. Or maybe not. Anyway, there are some things that I had to ask myself as I wrote this all down:

But isn’t hunger/poverty/whatever a good creative motivator?

Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t (see my post on this here). But this isn’t about “making it” as an artist, necessarily (though it certainly could be); it’s about literally surviving off your own work. It’s not about becoming great whilst (or even as a result of) stealing bread and sleeping on the street, but about using whatever greatness you already possess to buy bread, pay your rent, and get by. It’s simply meant to be proof that you can, if that’s what you want to do.

Okay. But by making it as much about money as the creative output itself, aren’t you somehow tainting your work? Aren’t you basically selling out, on a minute scale?

This is really where the word “sustainability” comes in. This whole idea is fundamentally about sustaining yourself, as a creative-type, so that you can create more. Ultimately it’s always about the creative output, and the act of creating, not about the money; the money is simply what allows that process of creation to occur unfettered.

This is all very theoretical. What’s the end result?

The end result is whatever you want it to be. In theory this is a limitless idea. That’s the beauty of it. In practice, it may have more limitations than I currently anticipate. But we’re going to find out, and we’re going to let you know. In the meantime, please check out the Man (hat on) site, and follow our progress, and be a participant in this crazy idea.

Posted in Art, Inspiration, Money, Travel, Writing | 4 Comments »